In part one of this series, Tony Watkins introduced the concept of modality and multimodality. In this article, he develops these ideas to focus more explicitly on communicating through digital media. This is applied particularly within the context of Christian mission and ministry, but these principles are not distinctively Christian. They apply to any kind of digital media communication – for a business as much as within a church.

The two factors which shape our messages

As I wrote in the previous article, the very simple model of communication is inadequate. It assumes that the conversation partners hear everything clearly and understood each other perfectly. This is far from the truth, as is clear within a social semiotic theory of communication.

It seems that the common idea of communications in many churches is:

- there is a message which it is our task to communicate (and we know exactly what that message is)

- there’s an audience out there which needs the message

- so we need to use some kind of technology to get our message to those people

The assumption here is that, if we have done this, we have succeeded in communicating. That is simply not good enough.

First, this ignores how the message we intend to communicate is not simply an objective entity – a ‘thing’ which is entirely external to us. We bring something of ourselves to any message we communicate, not least because it is always the result of us encountering prior prompts and interpreting them. What we shape into our message is our perspective on the subject, and that depends on our interests, knowledge, cultural context, and much else. Even the question of what we choose to communicate is rooted deep in our interests.

Second, however we communicate our message, we cannot assume that everybody has seen, read or heard it, never mind understood it. As we saw in the previous article,

- communication happens in response to a prompt, but the prompt can be ignored by a potential recipient

- communication happens when there is an interpretation (by the recipient), but the interpretation may not be in line with what the initiator of the communication intends

So the two factors which shape all our communications are:

- our interests: the ideas we want to communicate, our understanding of those ideas, and our preferred design approaches and technologies

- our understanding of the audience: their interests, prior knowledge, and preferred design approaches and technologies

Of course, we never understand the audience fully. We think we know our audience, but often make huge assumptions about who is reading or watching our material. We tend to think of our audiences too generally. We are rarely specific enough in our thinking, so we end up not targetting our message very well. A scattershot approach of trying to communicate to everybody doesn’t connect well with anybody. A targetted communication to a well-understood target audience will connect well with them, but can also connect with others outside of the target group. Having constructed a message based on our interests and our understanding of the audience, we have more chance of capturing the recipient’s attention and their engagement.

Four key aspects of digital communication: the CAST model

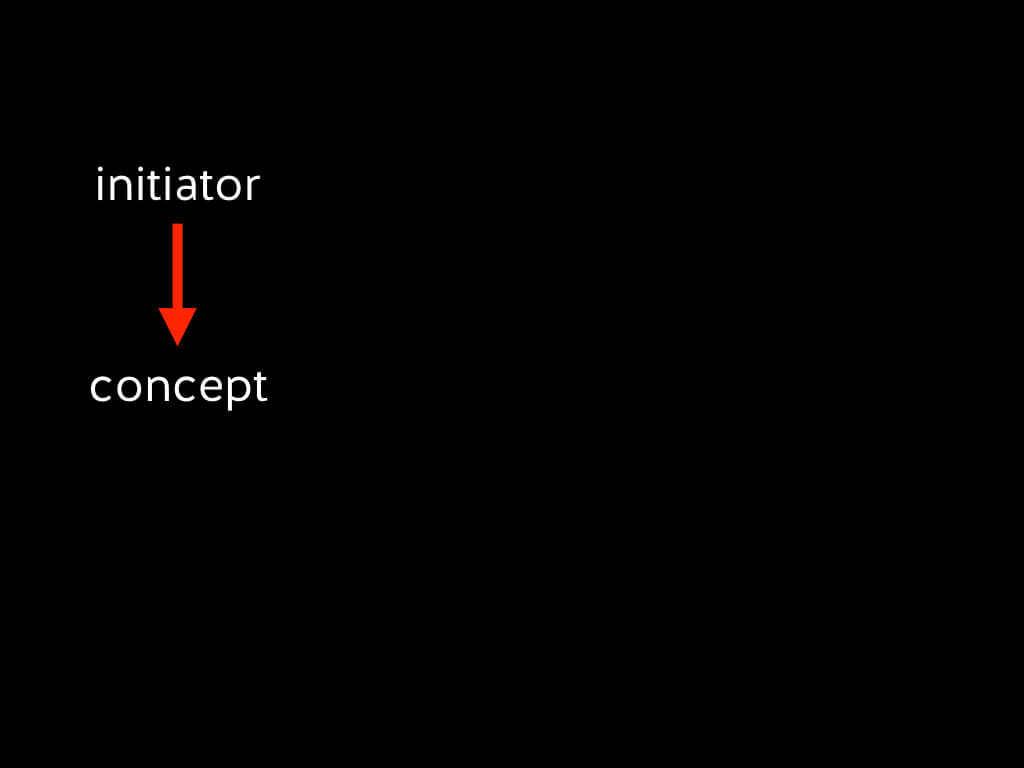

The model of communication I have developed1 has four key aspects, which help us to reflect on important stages of the communication process.

I call this the CAST model of communication: Concept, Audience, Shaping, Transmission.

1. Concept

Before we ever start constructing the message, we have a concept. Where does this concept come from?

The initiator of the communication sets the ground (provides a prompt) for the recipient to do some interpretive work, but the initiator is not creating a message ex nihilo – from nowhere. We do not come up with ideas in a vacuum. The ideas have come from somewhere. The initiator acts in response to things he or she has already encountered – a prior prompt: something she has read or seen, or which came up in a conversation, or in her reflections on scripture. The initiator will have done interpretive work on this prior prompt.

This article, for example, does not pop out of nothing in my mind. It results from my previous reading of books on communication theory, my experience of communications, and my reflection on both theory and practice. I was the recipient of prior prompts provided by many writers and have done interpretive work on them. I eventually took the results of my interpretive work and fashioned them into a new sign complex (a set of signs – this article and the accompanying images) which points to the meaning I want to articulate. I have then offered to new recipients (you, the readers) as a prompt for your attention and engagement. I have set the ground for your interpretive work.

We encounter and respond to prior prompts and interpret them. We develop these in our minds into a new concept – based on our interests, as we saw above – which we want to communicate to others. Then we shape that concept into a message. But if we launch straight into shaping the message, we are likely to ignore the second factor mentioned above and not give sufficient thought to the people to whom we are communicating. So the second aspect to consider is not the shaping of the message, but the audience.

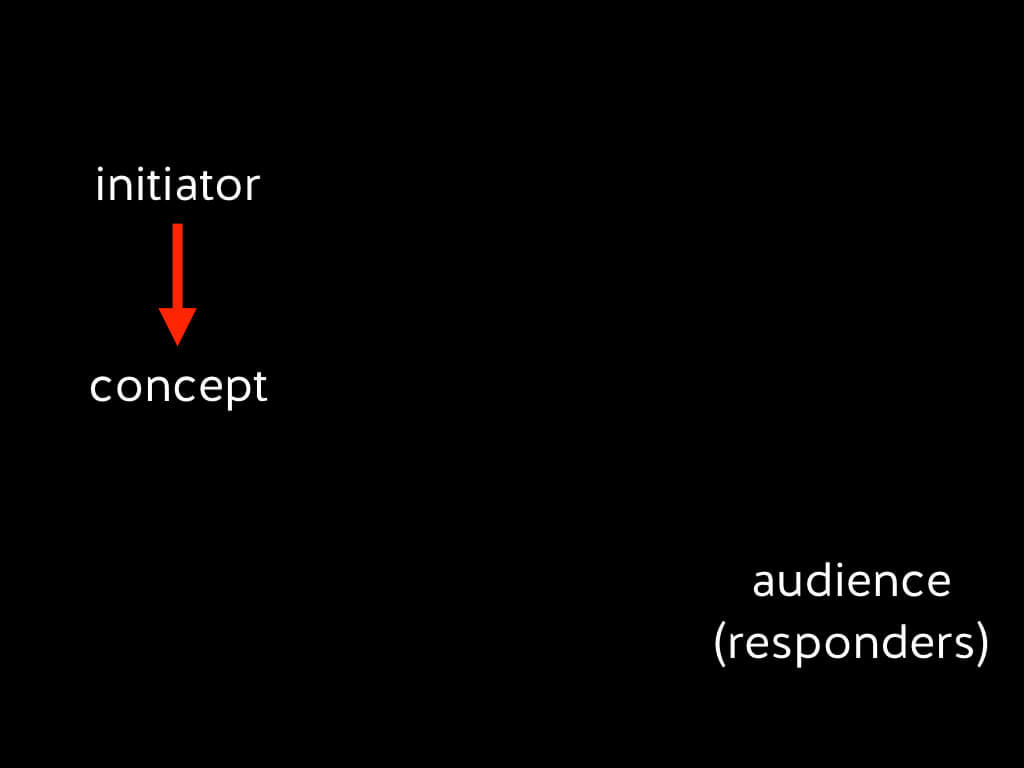

2. Audience

The second aspect of the CAST model is the audience. The audience is the end of the process in one sense, but it must never be the last point in my thinking. If I simply work sequentially from me to the audience, I am only considering the communication with reference to my interests, not to my audience’s needs: What concept do I want to communicate? What do I think would be a good way of shaping this message? What do I want to use to transmit this? Such me-centred communication is never appropriate for Christian communicators.

Once I have my concept, therefore, the next stage is to consider what is best for my audience, not what is my preferred way of communicating it. That is likely to mean that I need to work much harder on shaping and reshaping the message to make it suitable for them.

We must work hard to understand our audience rather than making assumptions about them. Consider factors like their

- culture

- socio-economic background

- gender

- age

- literacy

- language

- technological competence

- use of social media

- occupation

- leisure activities

We need to consider how our audience is likely to respond2 to the concept we are communicating and to the way we shape the message.

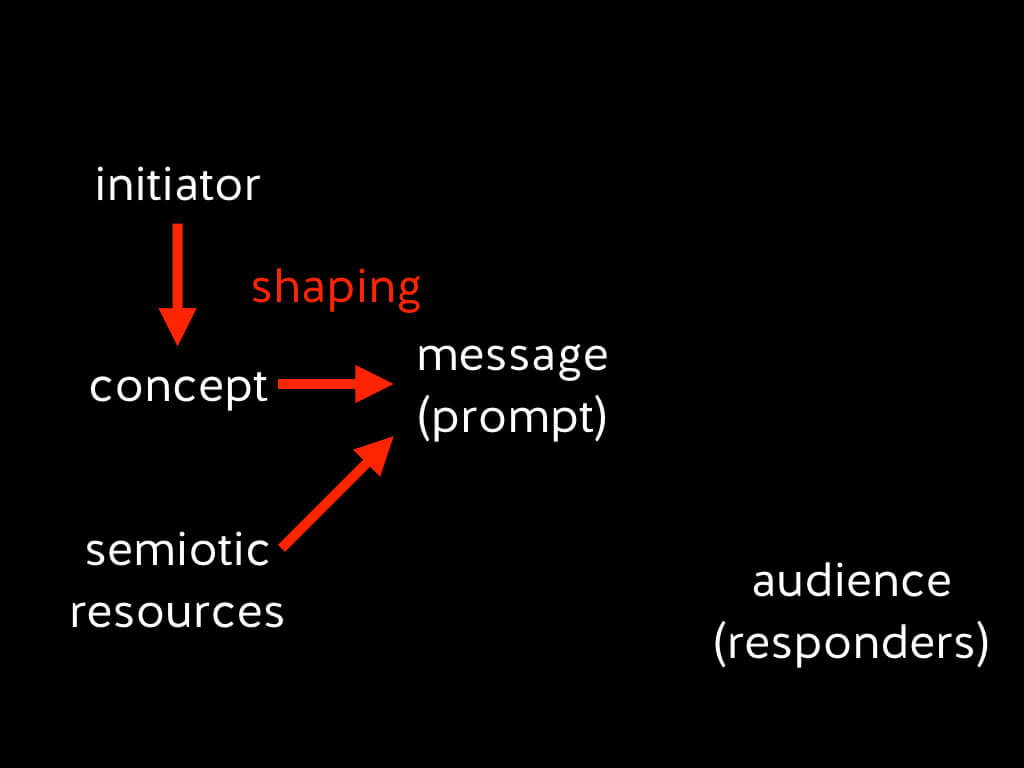

3. Shape

Once I have a good grasp of the concept I want to communicate, and a good understanding of my audience, I can begin to construct my message in a form which my audience can respond to.

To construct the message, we will draw on various semiotic resources: there are signs and modes available for us to use. The available semiotic resources and the concept itself need combining together to create the message. This is the process of shaping.

We need to do our best to shape our message in the best possible way so that our audience will engage with it, understand it, and respond to it. The goal is that their lives are changed. This is the point of Christian communication: not that we can be self-satisfied about our communication strategy or social media presence, but that God’s kingdom grows. So how do we shape this message in order to bring about changed lives? What is the best way to shape my message for this audience?

I need to ask questions like:

- What ideas do I need to include?

- What are the best words for me to use?

- What is the best mode to communicate this – speech, written text, video, etc.?

- How do the signs I might use function in my audience’s cultural context

- What images will work?

It is vital, as part of this, to think about which modes provide the most appropriate affordances. As we saw in part one of this series, affordances are the qualities a mode has – what it enables you to say. A handshake is a good mode for communicating ‘welcome’ or ‘it’s good to see you again’ or ‘we have agreed’, but no good at all for communicating ‘I’m confused’ or ‘that’s a beautiful sunset’.

We need to consider, then, which mode or modes will give us the combination of affordances we need to be able to communicate our concept effectively to the audience. If we want to express love to someone, we will want to have a wide range of affordances at our disposal. Sending messages via Morse code might be amusing (or even necessary in some circumstances), but is hardly likely to lead to a rich relationship. A handwritten letter has more affordances than a text message; a conversation over dinner has more affordances than a telephone call. But if we are communicating within the context of, say, a television news programme, a dinner-table conversation has the wrong affordances altogether. Instead, we need to be able to communicate seriousness, thoroughness, and impartiality.

Which affordances do we need, and therefore which modes should we be using, when communicating the gospel? It all depends on the context. A radio ministry, by definition, primarily uses broadcast speech. But the broadcaster can make its communication multimodal by including music or drama in its programmes, or by making use of social media or printed resources. Yet when communicating the gospel within a friendship, these modes may not be ideal.

Having decided on the modes with the most useful affordances, we then need to decide on what signs to use within each mode. We need to find the best words, the clearest or most potent images and symbols, the colours with the right psychological connotations, and so on.

The key question to ask is, how do I shape my message so that it best serves the needs of my audience in order for them to understand my message?

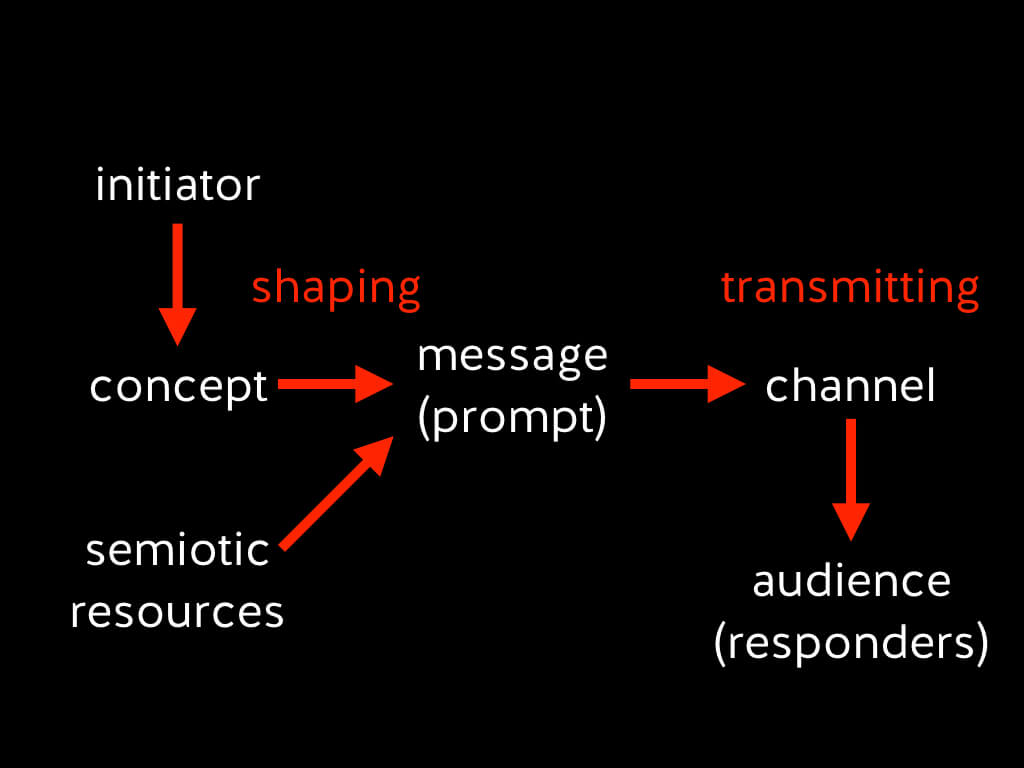

4. Transmission

Having shaped the message, we need to pass it on to our audience – to those we hope will be responders – through some kind of channel. This is the process of transmission, which is the final aspect of the CAST model. This is not necessarily in the sense of broadcasting, since in a face-to-face conversation we are still transmitting our message to the other person.

In the case of this article, since the means of transmission is the internet, I shaped my concept using the primary mode of text, but included some other modes: photographs, diagrams, and symbols. These can all easily be transmitted electronically via the internet and whatever web browser you are using to read this. Previously, this material was a lecture so the means of transmission was me speaking in a lecture theatre while projecting things on a screen. On that occasion, I combined the modes of speech and gesture as well as text, photographs, diagrams, and symbols. At some point, I could re-shape it again into a video presentation for transmission via YouTube.

The transmission aspect raises technological questions:

- What technological tools and channels are available to me?

- Which can I use well or easily or cost-effectively?

- What technological tools and channels can actually reach this audience most effectively (which we may measure by numbers of people in the audience, or by the impact on them, or both)?

- Which are the most appropriate for this audience?

Summary

The process of communication is, as we have seen, very complex. As Christian communicators, we have a responsibility before God to do it to the very best of our ability. And we have a responsibility to our audience to do our best to communicate our message to them as clearly and helpfully as we can so that their lives can be changed. If we fail to do so, it is a failure to love either God or our audience or both.

The CAST model of communication helps us carefully consider the whole process. We start with our concept and work on that until we have the best understanding of it we can. Then we work to understand our audience as well as we can, so that we can work hard at shaping the message in the best possible way to suit both our concept and our audience. And finally, we must think carefully about how best to transmit our message so that our audience can encounter the message – recognise the prompt, engage with it, and do interpretive work on it.

The ultimate goal in all this is that lives are changed to the glory of God. That is a wonderful goal.

Share this Post

Photo credits (from top):

© Aleksi Tappura. Image from Unsplash.com.

© Ariane Hackbart. Image from Unsplash.com.

Diagrams by Tony Watkins

- My model draws on, but substantially reconfigures, a model outlined by Gunther Kress in Multimodality: a Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication (London: Routledge, 2009). ↩︎

- Note that, from here on, I will generally refer to the audience as ‘responders’. Kress refers to the audience as both ‘recipients’ and ‘interpreters’, but in my view the word ‘recipient’ is too passive unless some interpretation also takes place. The more active word ‘responder’ can cover both of those aspects. ↩︎