In the fourth part of this six-part series on using films in Christian communication, we look at the second of the five key dimensions of worldviews. This series was first published on www.tonywatkins.uk, and is based on lectures given at Gimlekollen School of Journalism and Communications, Kristiansand, Norway. The series is available to download as a PDF.

Worldview dimensions, continued

Humanity

The second key aspect of worldviews is the nature of human beings. What does it mean to be human? This is closely bound up with the question of reality, of course. Are we simply physical beings – very clever animals or biological machines – or are we also spiritual beings? What happens when we die? The question of our identity – what and who we really are – is so important to us that is vital to reflect specifically on what films say about the matter.The possibility of a spiritual dimension to human beings is obviously often explored in films which are about death. The Lovely Bones (Peter Jackson, 2010) is about the abduction, rape and murder of a twelve-year-old girl, Susie (Saoirse Ronan). Much of the film is about her experiences after death. She is in limbo, a beauiful in-between state; she is dead but not in heaven, and often aware of what is happening in the world of the living. There is no mention of God in the film, yet it assumes that life continues after death and that we might go to heaven. This kind of God-free afterlife is what many people in western cultures now believe. They have rejected the traditional Christian belief in a day of judgment followed by eternal life or expulsion from God’s presence, but they don’t want to let go of the idea of heaven. It’s exactly what we get in Ridley Scott’s Gladiator (2000) which it concludes with a powerful death sequence in which the hero (Russell Crowe) is reunited with his murdered family.

What Dreams May Come (Vincent Ward, 1998) is primarily about the afterlife, following the death of the central character Chris (Robin Williams). He has made it into heaven because he was basically a decent man, not because of any faith. There is no indication of how he is judged to have reached the required standard; it’s simply a question of cosmic cause and effect, like karma. His wife Ann (Annabella Sciorra), however, commits suicide because of her unbearable grief and therefore ends up in hell, so Chris, feeling that this is unjust, sets out to rescue her. It seems to be a mixture of ancient Greek and eastern ideas of life after death, with a little Christian material thrown in for good measure. Chris Sinkinson says that, ‘Contemporary western culture is now trying to find a new concept of death.’ He notes that in What Dreams May Come and in Flatliners (Joel Schumacher, 1990): ‘. . . the experience after death is related quite directly to how we think in this world. The after-death world is a place of our own imagination and its contents depend upon the kind of moral imagination we have had. A suicide victim is portrayed as being in hell. The hell is of her own making as she has chosen a thought world of intense self-pity. Even in heaven, God is nowhere to be found in the world of What Dreams May Come? One character admits not knowing where God is but speculates; ‘He’s up there somewhere shouting that he loves us and wondering why no one is listening.’ The film portrays heaven as the product of our personal imagination and not the gift of a personal God.1

In eastern thinking, death leads to successive cycles of reincarnation until a state of nirvana, or enlightenment, is reached. It is still relatively uncommon in western cinema, though it is clearly present in the Matrix trilogy, particularly with the reincarnation of The Oracle (Gloria Foster/Mary Alice), and it is discussed in Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise (1995) and Before Sunset (2004). The most entertaining film about it is Dean Spanley (Toa Fraser, 2008), in which we gradually realise that the Dean (Sam Neill) had previously been a dog.

The nature of humanity is explored in other ways, too, of course. Cold Souls (Sophie Barthes, 2009) tells the story of a man (Paul Giamatti) whose soul is weighed down but who engages the services of a company which stores or exchanges souls. It is a biting satire on a materialist view of human nature and on the contemporary willingness to sell our souls in a bid to gain short-term happiness. What Paul finally realises is similar to what Joel (Jim Carrey) realises in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (Michel Gondry, 2004): that we must accept the bad aspects of life as well as the good to be authentically human. Suffering and pain are part of reality, at least in this world.

Clint Eastwood at the Toronto International Film festival, © Gordon Correll, used under a Creative Commons licence

Clint Eastwood has directed a number of films in recent years that very thoughtfully examine aspects of human nature and identity. Mystic River (2003) explored similar territory to Unforgiven (1992): the capacity for evil that lurks in the human heart, and therefore also the yearning for some kind of redemption (these also relate to other worldview aspects which we shall consider shortly). In contrast, Paul Thomas Anderson also points to the darkness within us in There Will Be Blood (2007), but with little or no sense of redemption being genuinely possible. Eastwood’s films seem to be rooted in a basically Christian worldview which highlights our fallenness, insists on moral absolutes and offers the possibility of redemption. There Will Be Blood, however, seems to suggest, when taking into account its mockery of religion, that there is nothing beyond us. Therefore there is ultimately nothing driving us other than simple self-interest, which expresses itself aggressively when the pressure is on. This is nihilism. Eastwood’s pair of films from 2007 about the Battle of Iwo Jima, Flags of our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima, both explore some of the tensions in human nature: our capacity for courage as well as fear, and our sense of responsibility to others as well as the instinct for self-preservation. They reflect the Christian view of human beings as being capable of immense good because we are God’s image-bearers, and of immense evil because we are fallen. More recently, Eastwood’s Gran Torino (2009) and Invictus (2010) have explored in very different ways the importance of realising that all human beings share a common humanity, and that we are at our best when we act for the good of others.

In part 5, we look at the three other worldview dimensions.

Share this Post

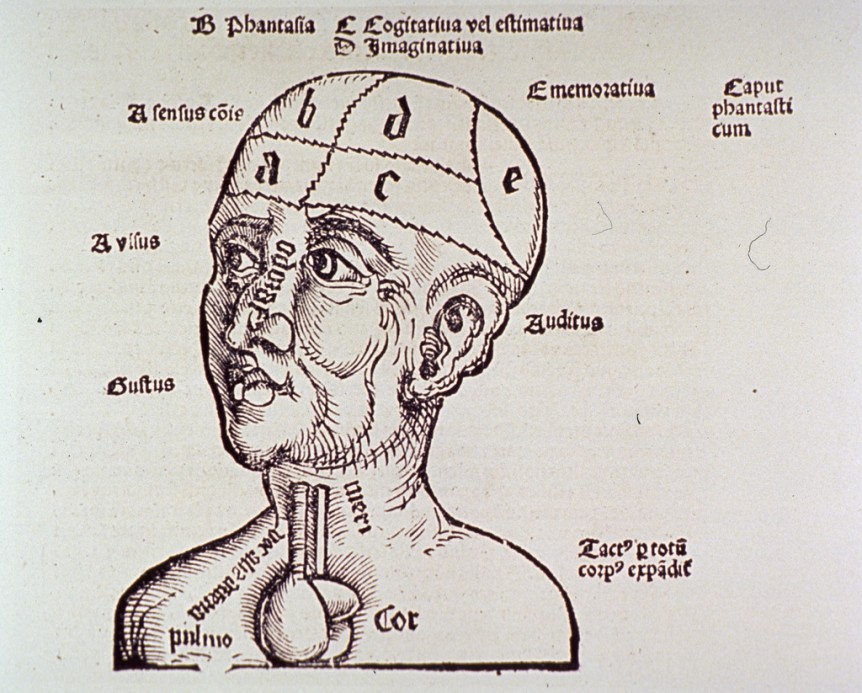

Photo credit: Public domain from Flickr Commons.