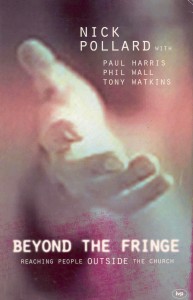

The final part in a three-part series adapted from chapters by Tony Watkins in Beyond the Fringe: Reaching People Outside the Church (Leicester: IVP, 1999), by Nick Pollard, Paul Harris, Phil Wall and Tony Watkins. Read part one and part two.

The final part in a three-part series adapted from chapters by Tony Watkins in Beyond the Fringe: Reaching People Outside the Church (Leicester: IVP, 1999), by Nick Pollard, Paul Harris, Phil Wall and Tony Watkins. Read part one and part two.

As the conversation goes on you become more and more anxious. You know you should say something but you just can’t think what. Probably all of us have been there at some time or other. What can we do about it? Think about when this happens. What kind of conversations are they? I think they fall into three main groups.

Personal issues

When something significant happens in people’s lives, they tend to talk about it. It could be something terrible like bereavement or divorce, or something exciting – a birth or a marriage. Or perhaps something less tangible – a sense of hopelessness or anxiety about the future. When these kinds of issues come up in conversation, there are plenty of things we can say as Christians, including, ‘Can I pray for you?’ The gospel speaks powerfully into these situations.

Issues in society

We also have many openings for presenting a Christian angle on wider issues in society. As Christians we should have something to say on inequality, sexuality, youth crime, homelessness, justice, and so on. Big issues of life find their way into our conversations. But all too often we do little more than share the same gloominess as everyone else. I remember all too well a conversation I had with my barber some time ago. Screen violence and its effects on society were in the news and we got talking about it. I may have said one or two helpful things, but the door was wide open for me to bring a distinctively Christian perspective. I could have talked about God’s view of violence; I could have talked about why people make violent films in the first place and what it betrays about their hearts; I could have talked about the consequences of us becoming anaesthetized to violence by seeing so much of it. But I didn’t. I was too embarrassed to clearly express my faith perspective, and we ended up just shaking our heads in despair at our society. One day we’ll come back to this issue and next time I hope I’ll be more ready.

Issues in the media

This one is perhaps less obvious to many of us. These are the conversations we have about what’s been on TV, the film we’ve just seen, or the book we’re reading. People talk about these things all the time. Nobody thinks it’s odd or ‘heavy’ if we bring them up in conversation. The problem we have is that our conversations about the media are often quite trivial, going no further than the commenting on the quality of the visual effects or which actors we like.

Every day we are bombarded with messages from all the media. We get up, check Facebook and Twitter, and perhaps listen to the news. Some people still read a newspaper over breakfast. The post brings a pile of junk mail, maybe a magazine and newsletters from various organisations. On our way to work we pass dozens of billboards (count them one day and then watch to see how often they change the posters).

At work there’s a whole raft of new messages to contend with, both in print and online. Over lunch perhaps we do some shopping and get presented with hundreds of brand names and products. On our way home we might listen to a commercial radio station in the car for the travel news, or we listen to music on our phones or iPods while on the train. After work we perhaps put our feet up and watch some television, at the same time as scrolling through various social media timelines on our smartphones, and will almost inevitably spend some time looking at various websites. How many adverts have we been exposed to during all this? How many other things have we read, watched and listened to, all of which are communicating messages to us?

We need to remember that what we read and watch and listen to carries many messages. Every book or film is written out of a particular worldview. The writer or director of a film may or may not be consciously expressing his or her worldview. Sometimes it’s very obvious what the worldview is (The Golden Compass, for example); sometimes the worldview is almost impossible to pin down – but it’s there nonetheless. As philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff notes,

Works of art are not simply the oozings of subconscious impulses; they are the result of beliefs and goals on the part of the artist. 1

Gradual shaping

Gradually, people build their worldview from all these messages. We start out with a worldview inherited from our parents. At school it may begin to change as teachers and friends bring other influences to bear on us. And as we grow up and receive more and more messages from the media, so our worldview gradually transforms into something which may be quite different from that which we started with. The messages we receive may or may not be consistent with a Christian worldview. Some things will have a positive influence and some will have a negative one.

These messages, these worldviews, influence us. It will rarely be a sudden, dramatic change, but is more likely to be a slow, subtle process like the gradual smoothing of rocks by the sea. Unless we actively evaluate these messages, over time our ideas of what is true and good and beautiful will shift. If this wasn’t the case, such massive sums would not be spent on advertising.

There is enormous scope for having very constructive conversations with people that relate to the media. Our biggest challenge is to get away from the trivia. If I’d got chatting with someone who wasn’t a Christian after watching Saving Private Ryan it would have been easy to have talked about the idea of sacrificing oneself for others. We probably would have discussed the rights and wrongs of the Second World War and war in general.

The Bible has plenty to say on such issues, and such a conversation would not have seemed strained. There is obviously some overlap between the three areas of conversation that I’ve outlined. Personal issues often arise out of what happens in the wider society. And books, films, music and TV are always dealing with the same kinds of issues, often with some particular angle on them. Of course, there are other types of conversation too. I am convinced that the gospel has something to say about everything. However, it’s not always easy to make the connection without coming across as rather false. If you link the gospel to a friend’s recent fishing trip you’re likely to sound a little corny.

Some people could get away with it but it would seem very cheesy if I tried it. Some conversations lend themselves, then, to bringing in a Christian dimension. But what then? It’s all very well knowing that this is the kind of conversation where we may have an opportunity. The question is how do we do it? There are three important factors to work on if we want to get better at this.

Know the gospel

It is vital to know the gospel well. We have no excuse for not knowing what we believe. We are Christ’s ambassadors (2 Corinthians 5:20). Would any ambassador not know his country’s foreign policy? If Louis de Bernières’s portrayal in Captain Corelli’s Mandolin is historically accurate, the Italian ambassador to Greece during the Second World War was totally ignorant of Mussolini’s intention to invade Greece. This points to the craziness of Mussolini’s actions, because we know that ambassadors aren’t generally kept in the dark. They know what’s going on. And they don’t hesitate to stand up for their country when there is an international incident. God has entrusted to us the ministry of reconciliation (2 Corinthians 5:18–20). We need to know how that reconciliation comes about.

Learning a gospel outline is helpful. These are best used as a framework for what we need to say, not for reciting parrot fashion. ‘Two Ways to Live’, ‘The Bridge to Life’, and similar outlines are extremely useful tools to help us in our evangelism. But they cannot substitute for knowing the good news of Jesus Christ well enough to communicate it clearly and simply. It’s not just the core of the gospel we need to know; we need to get to know all of God’s word better.

The gospel is central to the whole Bible. We need to understand Jesus’s life, death and resurrection in the context of the whole of God’s revelation. We also need to know God’s Word better so that we can identify the Christian response to issues. That’s not to say that the Bible directly addresses every issue that we come across. It doesn’t say anything specific about genetic engineering or western democracies, for instance. As we get to know God better through meeting him in his Word, however, we will develop a sense of which principles relate to these questions.

Know what’s going on

Christians should be up on current events. We should think about what the gospel has to say to those situations. We need to demonstrate genuine, godly compassion for a world in a mess, arising out of God’s great compassion for us. We can’t go to every situation and help, but we can pray and give. We should read our newspapers on our knees – and not because the broadsheets are unmanageable any other way. We should also be aware of the current events in the lives of our friends and colleagues.

I’m not suggesting we should pry into their lives. Nor should we get involved in gossip so that we know what’s going on. But we should be taking time to get to know people. We should have the time to ask how they are, and to listen to their response. We should be alert for signs that all is not well, and demonstrate Christ’s care for them.

When we meet others, the big issues of the day and the big issues of personal life do come up in conversation. Whether it be yet more conflict in the Balkans, a scandal involving a public figure or ongoing trauma with a rebellious teenager, we are likely to discuss it with our friends. If we are ignorant and indifferent to these things, we do no one any favours. But if we are genuinely concerned and have a real compassion for those who are caught up in these situations, it shows through. And when it does so, people have a small glimpse of the compassion of God.

Know what people think

Know people’s beliefs and values and where they get them. We have seen how Paul understood the beliefs that were under the surface of the culture of Athens. When he talked to people he genuinely engaged with their ideas. He affirmed some aspects of their worldview as having some truth. But there was also error, and Paul ensured that he exposed it. He showed that there were weaknesses in what they believed and then went on to talk about Jesus. His evangelism was true to God’s Word. It was also relevant to their culture. In our society people don’t sit around in the market place discussing their ideas about life; they sit in the pub or the canteen at work. They don’t tend to read much philosophy and poetry. They read novels and magazines. They watch films and TV. They listen to popular music and surf websites.

These are the sources from which most people pick up large chunks of their basic beliefs and attitudes. We need to understand others’ beliefs. We should also understand where and how they get them. We need to be aware of the messages people receive from what they watch and read. And we must be able to show them why those messages are poor substitutes for the good news of Jesus Christ. As long as they’re happy with the worldviews they already have, they won’t want to listen. But if we can help them begin to see the weaknesses, they will begin to understand that they need the Gospel.

Hannah was a student on a conference at which I was speaking. She told me about her housemate who was trying to base her life on the ideas in James Redfield’s books. His first, The Celestine Prophecy (Bantam, 1994), purports to be the story of the discovery of an ancient Peruvian manuscript (written in Aramaic which is, apparently, how they knew it was genuine – if that makes any sense whatsoever!). This manuscript contains nine insights for living life to the full. It’s very spiritual, some of the early insights seem to make a lot of sense, it’s very attractive and it addresses some of the needs we’re aware of. But, while there’s plenty in it we can affirm, at the end of the day it’s New Age thinking that will leave its followers living out a lie. Hannah and I talked about the ideas in the book and some of the problems with them. For one thing, it doesn’t have any concept of the sinfulness of human beings.

Any worldview that doesn’t allow for this is going to end up as a big disappointment when it can’t really explain why things keep going wrong in our lives. One day Hannah’s friend will discover that while she might feel more relaxed or energised, she’s still the same person with a load of guilt that needs to be dealt with. As we talked through James Redfield’s ideas it was clear to us that while they addressed real needs, only the gospel could adequately deal with them because only the gospel deals with that fundamental problem of our rebellion against God. I hope Hannah was able to have a similar conversation with her friend afterwards.

We often read the same books and watch the same programmes as some of our friends, neighbours and colleagues. If we’ve thought hard about them we have more chance of being able to relate the gospel to them when they come up in conversation. Some time ago Jane and I went to a friend’s for dinner. A colleague of his came too – a very bright professor, but not a Christian. During the evening I confessed that I’d been to see Spiceworld the Movie (all in the cause of understanding the culture!). He was surprised that there was anything of substance in it. I told him that I didn’t think there was, really.

But I went on to say that this is the point of the film. Image is everything; substance is immaterial. The film was an attempt to boost a career that was beginning to decline. It showed the Spice Girls as being young, fun and cool; people who love their music but don’t take it or anything else seriously – not even themselves. We went on to have a long serious conversation about how our society is obsessed with image and how nothing is taken seriously. We talked about hedonism, morality and the point of life. He didn’t end up on his knees in repentance at the end of the evening. But we did consider some huge questions that will make a follow up conversation with him so much easier. But this brings us back to our tightrope.

Starting where people are

Should a Christian ever read something like Ben Elton’s Popcorn or Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary? Or watch a film like Spiceworld the Movie or The Shawshank Redemption? Should we go to a lecture by Richard Dawkins? Some Christians reply with a resounding ‘No’. They’re concerned, rightly, that Christians should not conform to the culture. The world should notice that we have different standards. They remind us that we may be in the world but we are definitely not of it. But we must not isolate ourselves either. As we’ve seen, both conforming and isolation wreck evangelism. If people are to hear our message, we must speak it relevantly and engagingly. We cannot afford to be ignorant of what shapes our listeners’ most basic beliefs and attitudes. What they read, watch and listen to influences them. So, to understand the people, we must understand how these things do influence them. Then we must be able to engage with them at a suitable level.

We need to start where people are at and build a case for why they need to consider Christ. Too often we don’t do that. Why? We don’t know what the right starting points are. We don’t know how to catch people’s attention. We don’t understand their worldviews well enough to recognize their problems. We must recognize when someone is asking the right questions or is groping towards some answers. And we must also perceive and challenge wrong answers and wrong perspectives on life. Andy, who works with students, was involved in a group which discussed films and books together. At one of the group meetings they had been discussing Douglas Coupland’s book, Girlfriend in a Coma (Flamingo, 1998). Afterwards, Andy went to the university Students Union where he got into conversation with a student who wasn’t a Christian.

The student told Andy that he was reading a great book called Girlfriend in a Coma which was asking the same kinds of questions as he himself was. Is there a meaning to life. What is it? Is the world a place of hopelessness, or is there something that can give us hope? Is there such a thing as The Truth? Andy had a great conversation because these are the kinds of questions that the good news of Jesus Christ answers clearly. The big opening came because Andy had read and thought hard about the same book.

So, does that mean it is OK for Christians to read and watch what others are reading? Well, yes and no. The Bible insists that we must watch our life and doctrine closely, and that will rule out reading some things and watching others. But at the same time it is, at least to some extent, a vital task for anyone who longs to see the gospel really hitting home. It’s important to remember that we’re not talking about the really offensive material that’s out there. What we need to engage with is the normal, everyday stuff of culture that people, including ourselves, read and watch as a matter of course.

Most of us watch many of the same television programmes as our friends. We read many of the same books. We see many of the same films. We listen to the same music. And just like our friends, we do it all for entertainment. What I’m saying is that we should start thinking about all the messages that come into our brains and those of our friends day after day. We need to evaluate these messages, for the sake of both our discipleship and our evangelism.

The vast majority of the influential ideas come through sources that we wouldn’t struggle with very much. Having said that, though, some material is more problematic. I am not suggesting that we should all start reading and watching unhelpful things for the sake of the gospel. Francis Schaeffer once gave a lecture on Henry Miller and was asked afterwards, ‘But are you saying that we’ve all got to read these dirty books?’ Schaeffer replied, ‘No, but some of you have got to.’ At least some people within the church need to evaluate some things on behalf of the rest of us. And there are some things that we know enough about before we start that we leave well alone. Not everyone needed to see Spiceworld, but some did because that’s the world of those we are trying to reach.

Not everyone needs to engage seriously with Richard Dawkins, but some of us do if he’s influential on our friends and colleagues. Someone needs to read and watch and understand because they shape the culture we live in now. Whether through being acute observers and listeners of those around us, or through careful study, we must know how to respond to the beliefs, ideas and values of our friends, our colleagues and our neighbours.

John Stott writes of the need for Christians to engage in ‘double listening’. Let me quote one section at length.

How, then, can we be both conservative and radical simultaneously, conservative in guarding God’s revelation and radical in our thoroughgoing application of it? How can we develop a Christian mind, which is both shaped by the truths of historic, biblical Christianity, and acquainted with the realities of the contemporary world? How can we relate the Word to the world, understanding the world in the light of the Word, and even understanding the Word in the light of the world? We have to begin with a double refusal. We refuse to become either so absorbed in the Word, that we escape into it and fail to let it confront the world, or so absorbed in the world, that we conform to it and fail to subject it to the judgement of the Word. Escapism and conformity are opposite mistakes, but neither is a Christian option.

In place of this double refusal we are called to double listening, listening both to the Word and to the world. It is a truism to say that we have to listen to the Word of God, except perhaps that we need to listen to him more expectantly and humbly, ready for him to confront us with a disturbing, uninvited word. It is less welcome to be told that we must also listen to the world. For the voices of our contemporaries may take the form of shrill and strident protest. They are now querulous, now appealing, now aggressive in tone. There are also the anguished cries of those who are suffering, and the pain, doubt, anger, alienation and even despair of those who are estranged from God. I am not suggesting that we should listen to God and to our fellow human beings in the same way or with the same degree of deference. We listen to the Word with humble reverence, anxious to understand it, and resolved to believe and obey what we come to understand. We listen to the world with critical alertness, anxious to understand it too, and resolved not necessarily to believe and obey it, but to sympathise with it and to seek grace to discover how the gospel relates to it. . . .

‘Double listening’, however, contains no element of self-contradiction. It is the faculty of listening to two voices at the same time, the voice of God through Scripture and the voices of men and women around us. These voices will often contradict one another, but our purpose in listening to them both is to discover how they relate to each other. Double listening is indispensable to Christian discipleship and Christian mission. 2

This kind of studying and thinking is best done in small groups. Different insights and perspectives help everyone in the group to understand something more thoroughly. A group provides motivation to read further, for the purpose of understanding, not just enjoyment. It helps people think how to apply what they have learnt in their evangelism. And it brings a vital pastoral dimension as members pray for and support each other. That is useful when studying even the most innocent of non-Christian material. With some of the more challenging material it is vital. We also need to remember that this approach is just one aspect of evangelism. It’s the Spirit of God working in people’s hearts that converts them. It’s not a matter of how well we understand their worldviews or how well we answer their questions. It’s not even a question of how well we explain the gospel.

God must take away their blindness. But that doesn’t excuse us from knowing answers to tough questions, knowing the Gospel inside out and doing all in our power to make God’s word bite in the lives of our listeners. In the same way, we are not excused from knowing and understanding the beliefs and values,, the worldviews and cultures of those we are trying to reach. The Bible leaves us with a tension between doing all we humanly can and yet depending totally on God to do the work.

Paul knew that it’s only the Lord who saves people – yet it didn’t stop him from saying, ‘Since, then, we know what it is to fear the Lord, we try to persuade men (2 Corinthians 5:11). That’s why we must relate all our study of the culture around us to Scripture. It is the only solid reference point by which we can evaluate ideas. That’s why we need to pray through the implications for our evangelism of what we see in the books and films we study.

Studying our culture should equip us to use the Bible more effectively in our evangelism, whether preaching or personal, as we apply God’s Word to key points in the worldview of those we’re trying to reach. The Bible needs to bite the tender bits!

Stages in evaluation

We haven’t yet thought about what this looks like in practice. When we’ve watched a film or read a book, how do we evaluate it? Five stages are involved in thinking it through. It’s helpful to work through the same five stages when chatting with someone who does not share our worldview.

The Truman Show contains many links with Christian ideas. Truman Burbank is the unwitting star of a television show that runs twenty-four hours a day and is broadcast all over the world. Truman had been adopted at birth by the television company and had grown up constantly filmed by secret cameras. Everyone in Truman’s life is an actor. Only he doesn’t know.The town he lives in is in fact inside a huge studio.

One day Truman has a ‘Damascus Road’ experience. He sees the light quite literally when a stage light drops out of the sky in front of him with the name of a star painted on its side. Other slips in the management of the set make him suspect that life is not all it seems. Eventually he tries to escape by sailing off in a boat, the Santa Maria. After arranging a fearsome storm to dissuade Truman from his escape attempt, the director of the show, Christof, speaks to him from the sky. He tells Truman that he is the creator of the world that Truman knows, and that he has cared for Truman and has provided a safe environment for him. Truman is unimpressed – his whole life has been a sham; everything about him has been manipulated for the benefit of others. His ‘reality’ has been nothing but an illusion. Some of the Christian links are obvious. Christof’s name is not an accident. He is as God to Truman – a connection made more explicit by Christof’s declaration of himself as the creator.

But is this use of Christian ideas positive or negative? It is surely negative. Christof’s control centre is behind the moon in the roof of the set: the creator is the man in the moon. Christof is not a benevolent character but a manipulator. The environment he has made for Truman may be safe, but it is a deception; he has done all he can to prevent Truman from knowing the truth. It seems clear that Andrew Niccol, the writer, sees God (or the idea of God) in the same way.

If there is a God, he must be a despot. Maybe, suggests Niccol, the life we live is not the ‘real reality’, but is based on a lie because of its Judæo-Christian origins. We must escape to another reality, one without the man in the moon. It’s a message of the human spirit triumphing over circumstances to achieve freedom. The Matrix, written and directed by Andy and Larry Wachowski, also explores the idea that there might be an altogether different reality behind what we assume is normal life. Again there are many Christian links and it’s clear that the Wachowski brothers are not Christians. But they do seem to understand Christianity and to be somewhat sympathetic towards it.

This time the imagery is used for the good guys. Identifying the worldview isn’t just a matter of looking for links with Christian ideas and seeing if they are used positively or negatively. But it’s a good start. Whenever you read a novel, watch the TV or listen to an album, ask yourself, ‘What are they really saying about life? Where are they coming from?’

1. Identify the worldview

We need to identify what beliefs, values and attitudes underpin what we’re hearing. What view of reality are we being presented with? Where is the writer or director coming from? Where is this person coming from? The kinds of questions to ask are: What do they think is really real – just the physical world, or a spiritual dimension too? What do they believe about God? What does it mean to be human? What is the point of life? What happens when we die? What is right and wrong? How do we know? How do we know anything at all? What is the problem with the world and what’s the solution? (A useful book about current worldviews is James Sire’s The Universe Next Door, 4th edn. (Downers Grove, Ill: InterVarsity Press, 2004) Identifying the worldview (and the other steps below) is not just for a Damaris Study Group or when you’re particularly trying to understand a certain film or book. It should be something that we do constantly. Do you ever ask yourself about the values you see portrayed in Casualty or EastEnders?

2. Analyse the worldview

Having identified the beliefs, values and attitudes that are being communicated (or that shape the communication), we need to explore them a little more. Somehow we seem to think that it’s the Christians’ role in life to answer all the tough questions while everyone else gets to ask them. We’re constantly on the back foot in our evangelism, and being defensive. But we should go on the front foot and start asking tough questions of other ideas and worldviews. If we give others a chance to explore their worldviews a little more, they sometimes find that their ideas don’t hang together too well. If we’re considering a film, book or album, though, we will probably have to content ourselves with trying to work out for ourselves how the writer might answer the tough questions. For instance, Do the ideas hang together and make sense? Which ones do and which don’t? Do these ideas actually fit with reality? Do they describe the world as it really is? Or are they a distortion or invention? Do they ignore some significant factor? Do they work? What happens if you push these ideas a little further? What kinds of tensions and difficulties might they lead to? Where does it all come crashing down? In her book, The Whole Woman (Doubleday, 1999) Germaine Greer reiterates something she said in The Female Eunuch: men hate women. At least, all men hate some women some of the time. Many men would strenuously deny this. It should not be true of any Christian man. But is she right? Partly, yes, but she’s not telling the whole story, is she? This isn’t actually a gender matter. We should, in fact, extend her statement: all people hate at least some other people some of the time. It’s something that’s inherent in human beings since the fall: we are not always characterised by love.

Central to Ian McEwan’s novel Enduring Love (Vintage, 1998) is our perspective on life, especially our sense of right and wrong. The story opens with a balloonist and his grandson in difficulties attempting to land. The narrator, Joe, and four other men run to help. They cling to the ropes, but when a violent gust of wind suddenly blows the balloon and its human anchors over an escarpment, one of the men lets go. Now much lighter, the balloon lurches upwards and three others drop off to save themselves. One man hangs on, but finally and fatally loses his grip when the balloon has gained too much height. Joe is tortured by the question of whether or not he let go first and why the men let go at all instead of hanging on. He muses on the dilemma of whether to act altruistically or to save our own skins. McEwan says that selfishness is the ‘basic moral factor about ourselves’ and yet we also have this drive to co-operate. This, he says, is ‘our mammalian conflict’ – something we share with other mammals. Our mammalian conflict? We need to ask some questions at this point. Where is McEwan coming from? Apparently from a strongly atheist position which results in his seeing humans as no different from any other animal. Is the dilemma of altruism or self-interest a problem that all mammals face? It isn’t anything of the sort. It is a uniquely human conflict. There are other social animals, but human altruism goes way beyond a simple instinct to protect our group. Where would McEwan say this conflict comes from? From the pressure to survive? Does that adequately account for the strong human drive to care for others, even to sacrifice for them? A Christian explanation is that we humans have this conflict because we still bear the image of God. We instinctively know that others should take precedence. Yet because we’re fallen, the self wins again and again. Whatever you’re reading or watching or listening to, keep asking yourself, ‘Does this all add up?’ Like Paul in Athens, we can be positive when we agree and speak clearly against elements that are wrong. Every belief system, every book and film contains both truth and error. The Yin-Yang symbol, used by Buddhists and New Agers, is meant to symbolize the idea that in all light there is a little bit of dark and in all dark there is a little bit of light. Is this true? Sometimes: we are made in the image of God, and at the same time we are fallen and corrupted. But we can’t apply it to the whole of reality: ‘God is light; in him there is no darkness at all’ (1 John 1:5), while Satan is totally evil.

3. Affirm the truth

In the course of identifying and evaluating the worldview, then, we need to keep asking: ‘What is the good in this that we can happily affirm? What is consistent with a biblical Christian perspective?’ The ‘biblical Christian perspective’ part is crucial, for we have no other reliable way of assessing the rightness or wrongness of anything that we encounter. We certainly can’t trust our feelings alone. Douglas Coupland’s novel Girlfriend in a Coma is a powerful critique of the emptiness of modern living. We live in a hopeless society. Hope is something alien to many people today. It’s not hard to see some of the causes. The years following the Second World War were a time of rising wealth and optimism; we’d ‘never had it so good’. But the nuclear threat loomed ever larger. More and more environmental crises became apparent. As material prosperity grew, so did a sense of dissatisfaction. And now many people’s horizons have narrowed to just their own tiny world. Coupland’s characters are exactly at this point. They have no big picture of life, and no real hope. There are fragments of very immediate, personal, short-term hope. But nothing substantial (until towards the end, but I don’t want to give the game away!). It is a bleak view of life, and therefore true to the way many people really feel. Like Andy, who discussed Coupland’s book with a student, we can say, ‘Coupland has got it right. This is what people are like’.

In the course of identifying and evaluating the worldview, then, we need to keep asking: ‘What is the good in this that we can happily affirm? What is consistent with a biblical Christian perspective?’ The ‘biblical Christian perspective’ part is crucial, for we have no other reliable way of assessing the rightness or wrongness of anything that we encounter. We certainly can’t trust our feelings alone. Douglas Coupland’s novel Girlfriend in a Coma is a powerful critique of the emptiness of modern living. We live in a hopeless society. Hope is something alien to many people today. It’s not hard to see some of the causes. The years following the Second World War were a time of rising wealth and optimism; we’d ‘never had it so good’. But the nuclear threat loomed ever larger. More and more environmental crises became apparent. As material prosperity grew, so did a sense of dissatisfaction. And now many people’s horizons have narrowed to just their own tiny world. Coupland’s characters are exactly at this point. They have no big picture of life, and no real hope. There are fragments of very immediate, personal, short-term hope. But nothing substantial (until towards the end, but I don’t want to give the game away!). It is a bleak view of life, and therefore true to the way many people really feel. Like Andy, who discussed Coupland’s book with a student, we can say, ‘Coupland has got it right. This is what people are like’.

4. Discern the error

But we mustn’t forget to keep asking: ‘What is wrong in this, that we need to challenge? What is inconsistent with a biblical Christian perspective?’ Coupland has plenty to say about the spiritual dimension to life in Girlfriend in a Coma, but it’s nothing like the Bible’s portrayal of it. For Coupland, God is inaccessible, vague, remote and unknowable. Those who have died become ghosts that can interact with the living, even making them pregnant. There is no judgement. The dead, like the living, are a mixture of good and bad. I think Coupland is experimenting with his own beliefs and thoughts in Girlfriend in a Coma. They’re not really coherent, and he’s got the wrong end of the stick altogether about the spiritual realm. But he’s on the right track. At the end of the book he is sure that there is some Truth to be found. But he hasn’t the faintest idea what it is. He almost seems to suggest that the process of looking for the truth is more important than finding it. And he certainly has no conception that this Truth might be a personal, knowable God.

5. Identify a response

What is a good Christian response to these ideas? What would Jesus say in this situation? For many people, friendship with Christians is what prompts them to start searching for God. Seekers need someone to talk to them. They need to have someone evaluate their beliefs against the standard of Scripture. They need someone to help them construct a new worldview. A few people are interested enough to ask lots of questions about their Christian friends’ faith and come to Christ after straightforward conversations about the Gospel. But many are so wrapped up in their own worlds and so content with their current beliefs that they ask few questions. In those cases we must work hard to find points of contact and pray hard that God will break through into their lives. Where does all this leave us? Jesus has commissioned us to make disciples. To do so we must walk a tightrope between conforming to the world and isolating ourselves from it. The Bible maintains that balance throughout. It engages critically with other worldviews. It affirms the truth in them and denies the error. We need to maintain the same balance. We must know the gospel. We must understand the world in which we live. We must pray and keep on praying. Then God will take our lives, our words, our presentations of the gospel, and our critiques of others’ worldviews and, by his Holy Spirit, will do an astonishing work in their lives. We need to develop the mental tools to help people do what Paul did in Athens, and even to do what the Lord Jesus did when he stepped into human culture in order to redeem human beings. There is a world to be won and most of us need all the help we can get.

Share this Post