This six-part series was first published on www.tonywatkins.uk, and is based on lectures given at Gimlekollen School of Journalism and Communications, Kristiansand, Norway. The series is available to download as a PDF.

Life in the mediasphere

Sean Penn’s wonderful film Into the Wild (2007) tells the true story of a young man who abandons normal middle class life, gives everything away and hitch-hikes to Alaska where he plans to live in the wilderness. He wants to be surrounded by a beautiful landscape, not a cityscape. Most of us rarely stop to reflect on the landscapes or cityscapes where we live because our attention is largely captured by what Douglas Rushkoff calls the ‘mediascape’. The media surround us for most of our waking hours. We constantly consume radio shows, social media, websites, advertisements, music, television, magazines and more. Sometimes they invade our lives, whether we like it or not; other times, we actively turn to them for information or entertainment. They are so much a part of the background of our lives that we seldom play close attention. We forget what we see and hear almost immediately. Some media have a much greater impact, however. One in particular combines huge popularity with massive impact: film. It is true that many more people watch television than go to the cinema. But very many people buy or rent DVDs, or watch movies on television. There are very few television programmes which impact us as strongly as films do (exceptions include 24, Lost, The West Wing and a handful of others). There are plenty of poor films around, of course. But even watching a fairly average film is often a more memorable experience than watching most television programmes.Intense experiences

Why do films have such an impact on us? It is not just a matter of how much time we spend watching them. Rather, it is because of the way we watch them. We are intentional about it. We actively choose to go to the cinema, buy DVDs or stream movies on the Internet. It costs us in both time and money, so we feel cross when a film is poor. When we go to the local multiplex, we engage with the film even more actively than we do at home. Not only have we made a deliberate choice about what to watch, but the darkness, big screen and intense sound create a much more vivid experience. These factors combine to focus our attention – usually – in a quite intense way. With potent experiences like this, it is no surprise that films have a strong impact on people.

What films do to us

Films tell us stories which draw us in. They make us laugh and cry; they thrill us and scare us; they transport us to faraway places and bring to life things we could only dream of; they stretch our thinking and enable us to see life through different eyes. Films tell stories about characters with whom we identify to a greater or lesser extent. It may be because we feel we are like those characters, or it may be because we share similar goals. So, at some levels, films hold up a mirror, helping us to see something of what we’re like or what our society is like. However, films also shape us. We see ourselves and our world reflected back to us, but they are distorted reflections. We easily forget that what we see on screen is a distortion or, at least, a very narrow slice of reality. And then what we see gets into our heads and takes root, whether we realise it or not. Over time, the beliefs, values and behaviour we see on screen starts to seem normal, and our own beliefs, values and behaviour begin to subtly shift. Gradually the distorted reflection is less and less of a distortion.

Shaping worldviews

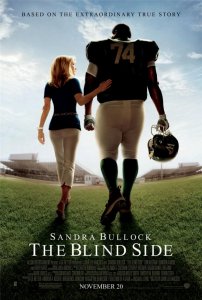

What this means is that films – and other media – influence our thinking, our values and eventually our behaviour. It usually happens gradually, but occasionally there can be a dramatic shift. A film like The Blind Side (John Lee Hancock, 2009), in which Sandra Bullock plays a Republican Christian mother who takes in a very disadvantaged African American boy, can inspire people to be compassionate to others. Although since 9/11, it seems that film-makers have become more obviously political, most of the time, film-makers are more concerned to tell a story than to actively promote their own beliefs and values. However, it is inevitable that their perspectives shape the stories they tell and the films they make. And as viewers, we take in at least some of the underlying ideas, whether we realise it or not.

What this means is that films – and other media – influence our thinking, our values and eventually our behaviour. It usually happens gradually, but occasionally there can be a dramatic shift. A film like The Blind Side (John Lee Hancock, 2009), in which Sandra Bullock plays a Republican Christian mother who takes in a very disadvantaged African American boy, can inspire people to be compassionate to others. Although since 9/11, it seems that film-makers have become more obviously political, most of the time, film-makers are more concerned to tell a story than to actively promote their own beliefs and values. However, it is inevitable that their perspectives shape the stories they tell and the films they make. And as viewers, we take in at least some of the underlying ideas, whether we realise it or not.

These underlying ideas and values are mainly communicated through the story itself: what actually happens and what is said on screen. But the way the story is told and filmed can also encourage people (perhaps in subtle ways, or maybe quite blatantly) to accept some perspectives and to reject others. Lord of War (Andrew Niccol, 2005) tells the story of an arms dealer, Yuri (Nicolas Cage), who loses almost everything yet learns nothing from the experience and goes back to arms dealing. Yuri experiences no redemption, and he is far from being a positive role model, but the way the film is made encourages us to recognise that his behaviour and attitudes are morally defective. In Creation (Jon Amiel, 2009), Charles Darwin’s friend, the local minister (Jeremy Northam), is portrayed quite negatively, reinforcing the feeling that science and religion are at war. Given the power of movies, it’s no surprise that they play a part in shaping our culture. Over time, they contribute to the weakening of some ideas or values which are prevalent in society, and to the strengthening of others. Expectations of love and romance in the modern world have, to a large degree, been created by the movies. Like it or not, films shape our thinking.

In part two of this series, I will begin to explore the subject of worldviews in films in more detail.

Share this Post

Photo credit: © Bartosch Salmanski. Used under a Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0) licence.