Part two in a three-part series adapted from chapters by Tony Watkins in Beyond the Fringe: Reaching People Outside the Church (Leicester: IVP, 1999), by Nick Pollard, Paul Harris, Phil Wall and Tony Watkins. Read part one.

Part two in a three-part series adapted from chapters by Tony Watkins in Beyond the Fringe: Reaching People Outside the Church (Leicester: IVP, 1999), by Nick Pollard, Paul Harris, Phil Wall and Tony Watkins. Read part one.

But Jesus didn’t tell us to simply preach the gospel. Our task is to help unbelievers become disciples – fully committed followers of Jesus Christ. How do we do this in practice? The Bible must be our guide. We will see that it engages with the world’s beliefs, values and attitudes and presents a powerful alternative to them. Right from the beginning, it takes engaging with culture very seriously.

The Bible and its cultures

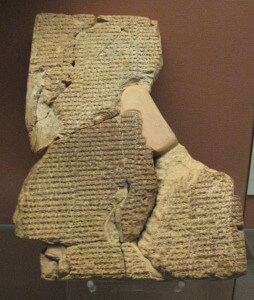

In the Old Testament, Israel had distinctive beliefs about God. These beliefs transformed (in theory) their whole way of life. This included their relationship with other nations. The first chapter of the Bible is a good example. It was written when Mesopotamia dominated that part of the world. People often point to links between contemporary myths and Genesis.

They claim that the writer(s) of Genesis based it on the Atraharsis Epic, Enuma Elish and other ancient myths. But actually Genesis is engaging with their ideas and correcting them. It directly attacks bad Babylonian theology. It affirms that there is one God not many (Genesis 1:1). It affirms that God is the creator of everything and that he created by the power of his word (Genesis 1:1,3). Compare that with the Babylonian gods who had to struggle to make the world after defeating the sea monsters (representative of chaos).

Genesis even goes so far as to tell us that God created the sea monsters (Genesis 1:21, NRSV; the NIV avoids referring to them as sea monsters and calls them “great creatures of the sea”). It insists that God created the sun and moon to serve us; they are not gods to be worshipped. Genesis doesn’t even give them their names; they’re just lights (Genesis 1:14–19).

This great chapter also asserts that humans are the pinnacle of God’s creation, made in his image (Genesis 1:26–30). For the Babylonians, humans were an afterthought of the gods who wanted servants to supply their needs. The Hebrews needed to get all this clear because false beliefs like these were all around them.

Much later the Babylonians carted Daniel off into exile (Daniel 1:1–7). They forced him to take a course at “Babylon University” in preparation for a new (compulsory) career in the Babylonian civil service. They were to be indoctrinated with Babylonian beliefs and practices. Nebuchadnezzar’s strategy was to strip away their cultural identity and make them faithful to him and his gods.

Right from the start, Daniel and his friends took a firm stand against certain elements of the culture in which they found themselves. But they also got stuck into the pagan literature, science (all expressed in terms of magic and astrology) and other learning that they were expected to take on board.

They weren’t going to keep their heads down and do the minimum to get by. Nor were they going to submit to Nebuchadnezzar’s plan to turn them into good Babylonians. They excelled at their studies to the extent that Nebuchadnezzar ‘found them ten times better than all the magicians and enchanters in his whole kingdom’ (Daniel 1:20).

This was the pattern of their lives from then on. They engaged with the culture but maintained their distinctiveness. Daniel rose to be ‘chief of the magicians, enchanters, astrologers and diviners’ (Daniel 5:11), a job title that we feel distinctly uncomfortable about. He must have been able to affirm some parts of the culture to do this.

But he continued to take a clear stand against other parts of it into his old age – even at great personal risk (Daniel 6). The Bible reveals a similar pattern the whole way through. Not everybody in it had to struggle with this issue in the same way as Daniel. Rather the Bible itself is walking the tightrope between engaging and keeping distinct.

As we saw, it has a dual function: to enable us to know God and how to respond to God. Our response must involve our mind, emotions and will – our whole being. The Bible doesn’t deal with either of these aspects by giving us abstract propositions. It doesn’t just give us stark statements of belief. Instead, God chose to reveal himself at certain times in history and in particular places. His Word comes to us via three specific languages (Hebrew, a little Aramaic, and Greek) and through the eyes of individuals with particular cultural outlooks. Compare this with Islamic, Hindu and Buddhist writings that are largely independent of some or all of these cultural specifics.

The Bible in our culture

The Bible negatively evaluates many aspects of the cultures within which it was written (e.g. Amos 3). But there are some positives too (e.g. Romans 1:14–15). Whether positively or negatively, God himself used the raw material of cultures to reveal himself to us. He even went so far as to step into one specific culture as a human being.

He was ‘made like his brothers in every way in order that he might become a merciful and faithful high priest in the service of God, and that he might make atonement for the sins of the people’ (Hebrews 2:17). We must somehow relate God’s Word to other cultures at other times, in other places and through other languages. Sometimes it’s easy (e.g. 1 Corinthians 13).

Sometimes it’s really hard: a passage like 1 Corinthians 8 doesn’t immediately apply to most of us in Britain. How can we make Scripture ‘zing and sting’ (in D.A. Carson’s memorable phrase) if we don’t know how those we’re trying to reach relate to its various aspects? How will we know that unless we’re familiar with their culture?

When their worldview is similar to ours we do this almost instinctively. Older generations in the West grew up with a broadly Christian worldview, even if they rejected it. When I did my teacher training, a friend and I shared a flat. In the flat above lived a man named Harry, who was in his sixties. He had long since rejected Christianity, but knew lots about it. There was plenty of common understanding that enabled us to have long conversations.

But the further a worldview is from ours, the harder evangelism gets. Evangelism among younger generations is a different ball game to a couple of decades ago. They have no Christian background. My wife, Jane, used to be a primary school teacher. Some time ago she took a group of children to their local parish church. One of the children was awe-struck at this building so unlike anything he’d ever experienced before. ‘Wow!’ he exclaimed, ‘This is a nice palace. Who lives here?’ If we want to reach a culture, we need to understand it. And to really understand it we need to enter into it in some way.

This is what God himself has done. Jesus gave up all the glory and holiness of heaven to get deeply involved with humanity. Even the best specimens of humanity are bad enough, let alone the prostitutes, swindling tax collectors and other assorted ‘low-life’ for whom he seemed especially concerned. This involvement is basic to all missionary work. It’s never enough simply to read books about something: you need personal experience.

We’ve accepted that this is true for cross-cultural missionaries for years. The big difference now is that evangelism to many British people today is also cross-cultural. Many in our churches haven’t yet caught on to this reality. It’s time we did. D.A. Carson writes: ‘As much of Western culture increasingly distances itself from its Judeo-Christian roots, the task of evangelism takes on the overtones of a missionary enterprise to an alien culture: part of the task is now bound up with understanding that culture’ (D.A. Carson, The Gagging of God [Leicester: Apollos, 1993] p. 491).

We don’t have the luxury of being able to preach a ‘simple’ gospel any more. People are biblically literate; they don’t understand the Bible and don’t want to. And they are on the way to an eternity without Christ. Luke records five major evangelistic messages in Acts. In four of these the audience was Jewish and therefore biblically literate. Peter twice addressed Jewish crowds in Jerusalem (Acts 2:14–41; 3:12–26).

Paul addressed Jews in Pisidian Antioch (Acts 13:14–43) and in Jerusalem (Acts 21:40 – 22:21). These audiences needed to see how Jesus was the fulfilment of all they believed. This has some parallels with the situation of thirty years ago when evangelism involved communicating to people who knew the Scriptures.

Paul in Athens

The fifth major evangelistic message is the one to the Council of Athens in Acts 17:16–43. This is the only significant evangelistic message addressed to Gentiles that Luke records for us.

Until this time, Paul had always gone to the synagogues to reason with the Jews and the God-fearing Gentiles. He did the same in Athens. But Luke makes very little of this. Instead his focus is on Paul’s discussions in the market place. Here his main audience knew nothing of the Old Testament.

Paul needed different tactics to relate the Gospel to them. Paul had time on his hands. He’d left Berea quickly, having almost provoked yet another riot (Acts 17:1–15). Now he had to wait some days for Silas and Timothy to join him. Despite his habit of being at the centre of riots, Paul didn’t keep his head down, catch up on sleep or walk the tourist trail.

He went to the synagogue as usual. But he also sat in the market-place day after day, talking with people there. In particular he disputed with some Epicurean and Stoic philosophers. Philosophy in those days didn’t have the kind of highly intellectual and obscure feel that it has today. Philosophy was a way of life.

Your philosophy was what you lived by, your worldview. The Epicurean and Stoic philosophies were the main worldviews in Athens at the time. Paul felt ‘greatly distressed’ to see how much idolatry there was (Acts 17:16). He couldn’t just let this go by. So he rolled his sleeves up, found a good spot and got stuck into conversations with others there.

On Mars Hill

Paul’s talk of Jesus and the resurrection provoked plenty of interest. Before long, the Areopagus (the council of Athens that met on the Areopagus, i.e. Mars Hill) wanted him to explain his teaching to them. Paul started by commenting that the Athenians were very religious (or ‘superstitious’; Paul may have intended both meanings), and used as his example their altar to ‘an unknown god’ (Acts 17:22–23). Paul could have spotted this altar in strolling around the city.

But notice that he says he ‘looked carefully’ at the objects of worship. He was not a casual observer, but was alert to potential bridges for the gospel. Paul could have used any one of a number of starting points. He could have launched straight into explaining why he was talking about Jesus and the resurrection to anyone who’d listen.

But he chose this particular opening because then he could root his message in his listeners’ worldview. That way he could get their attention in order to build a new worldview. He then worked through the doctrine of God and the doctrine of humanity and finished with a call to repentance. What Luke recorded for us is just a brief summary of Paul’s speech. It takes under two minutes to read it aloud. Paul would undoubtedly have gone on for much longer (this was the man who went on so long on another occasion that Eutychus nodded off and fell out of a window).

I once read that speeches in the Areopagus were often three or four hours long. Along the way, Paul quoted Greek poets and philosophers. The most obvious examples are the two quotations in Acts 17:28: ‘For in him we live and move and have our being’ (from Epimenides the Cretan) and ‘we are his offspring’ (from Aratus). It is almost certain that Paul used others during the course of his message given that we have two in this short summary.

In fact there are likely references to five others (Euripides, Plato, Posidonius, Cleanthes and Aeschylus) even in the summary Luke has given us. Paul was picking up on points where these Greek writers had got it right. They may not have had a biblical background, but that doesn’t mean their thinking was completely up the spout. Just because people are not converted doesn’t mean that they only think rubbish. Paul’s hearers were people made in the image of God who were asking serious questions about life, the universe and everything.

They were also finding some answers because, being in God’s image, they had access to some truth (Romans 1:18–23). The Epicureans had got some things right; the Stoics had other things right. Paul takes the trouble to affirm these things. This is a ‘powerful apologetic device that enables Paul to base himself on acceptable Greek theistic assumptions while at the same time going beyond them’ (Alister McGrath, Bridge Building [Leicester: IVP, 1992] p. 49).

Paul ‘knows the importance of establishing as much common ground with his audience as possible’ (F.F. Bruce, The Acts of the Apostles, rev. ed. [Leicester: Apollos, 1990] p. 382). What was Paul doing here? Was he trying to make his hearers think that there wasn’t much difference between him and them? Or that he went along with everything these Greek writers said?

Not at all. But ‘if men whom his hearers recognised as authorities had used language which could corroborate his argument, he would quote their words, giving them a biblical sense as he did so’ (F.F. Bruce, Paul: Apostle of the Free Spirit [Paternoster Press, 1977] p. 242). Paul was also careful to refute some of the Epicurean and Stoic beliefs. The resurrection is the major example. The people of Athens didn’t believe resurrection was possible.

In a play by Aeschylus, about the court of the Areopagus in fact, Apollo says, ‘Once dead, there is no resurrection.’ Everyone believed this. It’s this Athenian conviction that resurrection wasn’t possible that lies behind Acts 17:18, where they understand Paul’s talk of Jesus and the resurrection to mean two gods, Jesus and Anastasis (Greek for ‘resurrection’). Since resurrection doesn’t happen, Anastasis must be the name of a god who offers a fresh start in life.

Observing culture carefully

Marble altar dedicated to Hermes, Aphrodite, Pan, Nymphs and Isis, Athens. © Kevin, used under a Creative Commons licence

Where and when did Paul learn all this Greek poetry and philosophy? Did he simply quote what he’d picked up while chatting to people in the market-place? If so, he certainly didn’t pick it up casually. Luke tells us that Paul had ‘looked carefully’ at the objects of worship (Acts 17:23). He also debated with the philosophers; it was not idle chat. Paul listened carefully to what was said and genuinely engaged with it both in the market-place and in the Areopagus. Could he be quoting from material he had known since his youth?

Before his conversion Paul was a Pharisee. It’s hard to imagine him reading Greek poets then! But Paul was brought up a Roman citizen as well as a Jew, so it is just possible that he grew up reading Greek writers. Or had he been purposefully studying them for years? I think this is most likely. Paul was the ‘apostle to the Gentiles’. He was always ready to be ‘all things to all people so that by all possible means I might save some’ (1 Corinthians 9:22).

Surely he would have wanted to understand the cultures of the gentiles that he was striving to win for Christ. How Paul got to know Greek culture so well doesn’t matter very much. The fact that he did so matters very much indeed. The point is that Paul was very familiar with both the ideas and the details of Greek writers. He knew them well enough to do more than lob some everyday saying into his speech so that he could appear relevant.

He knew them well enough to engage with the ideas seriously, respectfully and yet critically. He understood the culture well enough to take his thoroughly Biblical message and express it in the thought forms, ideas and phrases that were part and parcel of that culture. He understood where his listeners were coming from well enough to move at least some from complete ignorance to faith.

Did Paul regret it?

But does Paul, as some people have suggested, then backtrack on this approach when he gets to his next stop, Corinth? Was his approach in Athens a mistake? Is this why only a few were saved? Is this why he wrote what he did in the opening chapters of 1 Corinthians?

Where are the wise? Where are the scholars? Where are the philosophers of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the world? For since in the wisdom of God the world through its wisdom did not know him, God was pleased through the foolishness of what was preached to save those who believe . . .

God chose the foolish things of the world to shame the wise . . .

When I came to you, brothers and sisters, I did not come with eloquence or superior wisdom as I proclaimed to you the testimony about God. For I resolved to know nothing while I was with you except Jesus Christ and him crucified. I came to you in weakness and fear, and with much trembling. My message and my preaching were not with wise and persuasive words but with a demonstration of the Spirit’s power so that your faith might not rest on human wisdom, but on God’s power. (1 Corinthians 1:20–21, 27; 2:1–5)

Not at all! There are several reasons why we can be sure of this.

- Paul’s commitment to preaching nothing but Christ isn’t new.

Paul always did this. What was the heart of his message in Athens? ‘Jesus and the resurrection’. The difference lay in how he presented his material not in what the material was. - ‘Nowhere in either Acts or Corinthians does Paul indicate any repentance or even regret over what he did on Mars Hill.

This is reading into the text what simply is not there,’ writes Norman Geisler (‘An Apologetic for Apologetics’). - In a subsequent letter to the Corinthians,

Paul describes his ministry as ‘demolishing arguments and every pretension that sets itself up against the knowledge of God’ (2 Corinthians 10:5). This is exactly what he was doing in Athens. - Paul must have preached ‘Jesus Christ and him crucified’ or his talk of resurrection and judgement would have meant nothing.

It just isn’t spelt out in the summary we have. Paul may have spent more time on the resurrection because Athenians didn’t believe it was possible. - Paul was experienced in evangelism in the Gentile world by this time.

His decision at Corinth would have been based on his assessment of the situation there. It was the administrative capital of the region and had a very unsavoury reputation. At the time, ‘to play the Corinthian’ meant to be sexually immoral. A place like that needed a different emphasis. This also explains Paul’s going to them in ‘weakness and fear and much trembling’ (2 Corinthians 2:3). - Someone so experienced in evangelism would not change his tactics just because only a few people were converted.

We jump easily to this conclusion because we are so ‘numbers-oriented’. We want to see lots of professions of faith. Sometimes it seems our credibility as churches hangs on it. This was not Paul’s outlook since it’s not a biblical criterion of success (e.g. Matthew 7:13-14). - How can Paul’s attempt to reach the thinkers of Athens be called a failure?

Think how far back his audience was starting in their knowledge of the God of the Bible. It’s incredible that any became Christians as a result of Paul’s brief stay in the city and one address to the Areopagus. Luke tells us that some believed (not ‘a few’ as many English translations have it; the word tines rarely has this sense for Luke).

Among them were Damaris and Dionysius. We know nothing more about Damaris, but church tradition tells us that Dionysius, who was a member of the Areopagus, became the first Bishop (or overseer) of Athens and there is no reason to doubt this. Although Paul used ideas from Greek culture quite happily, then, he never compromised his message. He didn’t get sucked into Greek culture, but used what he could of it, affirming truth and denying error whenever it was appropriate. When Paul wrote his second letter to Corinth, the church there was attacking him.

Some members thought that Paul and his team lived ‘by the standards of this world’. His reply is significant: . . . though we live in this world, we do not wage war as the world does. The weapons we fight with are not the weapons of the world. On the contrary, they have divine power to demolish strongholds. We demolish arguments and every pretension that sets itself up against the knowledge of God, and we take captive every thought to make it obedient to Christ. (2 Corinthians 10:3–5)

We live in a post-Christian culture, full of arguments and pretensions that set themselves up against the knowledge of God. Paul says they need to be demolished. Thoughts – ideas – must be made obedient to Christ. In the context Paul can’t be talking primarily about personal holiness, which is how we generally apply this verse, but ‘cultural holiness’. When ideas are in accordance with Scripture they can be affirmed. Where they are not, they must be brought into line.

Share this Post